The Secret History of France's Civil Nuclear Programme

How institutional design built energy independence—and why it couldn't last

I love secret histories. One that made a deep impression on me is Steve Blank’s Secret History of Silicon Valley, a collection of blog posts you can read here (or watch the 1-hour video version here).

Today, I'm offering you my secret history of how France, where I was born and grew up, became the world's most nuclear country, measured by reactors per inhabitant and nuclear's share of the national energy mix—not over decades but in merely 15 years! Between 1969 and 1986, France built literally dozens of reactors across 19 nuclear power plants, transforming from energy dependence to nuclear self-sufficiency whilst other nations debated and delayed.

By “secret history,” I do not mean that I had access to classified sources. Rather, I approach the topic through a different lens—focusing on institutions and geopolitics rather than science and technology—and I connect the available evidence in ways that, I believe, differ from most accounts of France’s nuclear programme. Many secret histories are not hidden; they merely remain unknown, either because no one looks closely enough or because they are examined through the wrong lens.

This story matters to everyone for three interconnected reasons. First, electricity demand is rising sharply as artificial intelligence and electrification reshape industrial systems. Second, reducing dependence on coal, oil, and gas for power generation has become both an environmental and strategic imperative. Third, today's fragmented and unstable world drives every nation towards resilience and reduced dependency, where nuclear energy offers a path to energy sovereignty.

There's also a deeper current running through contemporary debates about industrial capability and abundance. Many observers believe the West has abandoned its engineering culture to China, leaving both America and Europe unable to compete in a world where energy infrastructure and manufacturing capacity determine prosperity and security more than software and services. Nuclear power sits at the heart of this challenge—a technology that demands both engineering excellence and institutional coordination at scales that few nations have mastered.

France's programme succeeded not through technological breakthrough but through institutional design and engineering excellence. The country built a system that could execute complex, long-term projects whilst maintaining broad political support across changing governments. Understanding how France achieved this offers lessons that extend far beyond nuclear energy to any large-scale ambitious project powered by technology—from rebuilding manufacturing capacity to developing advanced infrastructure to coordinating national responses to technological change.

What follows is a tale of Napoleon-era engineering templars who became nuclear keepers, a Communist minister who consolidated France’s electricity grid under state control, Charles de Gaulle's grand strategic vision of energy independence, and a manufacturing approach that treated nuclear reactors like products rather than bespoke engineering projects. It is also a story of how success created its own constraints: why export markets destroyed the very advantages that enabled domestic triumph, how the Chernobyl disaster shattered public trust across the West, and how nuclear partnerships became entangled in geopolitical violence that stretched from the Iranian revolution through decades of terrorism, assassinations, and proliferation crises that persist today.

The complete story reveals the institutional fragility beneath technological triumph, why France's nuclear miracle cannot simply be replicated in our era of eroded state capacity and public scepticism, and what conditions would be necessary to recreate such ambitious programmes when governments struggle to maintain trust across the generational timescales that nuclear energy demands.

1/ De Gaulle built France around strategic autonomy

General Charles de Gaulle arguably stands as the most important political figure in modern French history. Born in 1890 to a devout Catholic family in northern France, he pursued a military career that seemed destined for obscurity until June 1940 changed everything. When the old and revered Marshal Philippe Pétain—de Gaulle’s former commander and hero—signed an armistice with Nazi Germany, the 49-year-old brigadier general felt such profound betrayal that he fled to London and broadcast his famous appeal of 18 June over BBC radio.

This act, though initially heard by few, established the principle that would define de Gaulle’s entire life: France must never again depend on others for its survival. From exile in London, he built a key part of the French resistance while rival networks operated inside occupied France. The Communist-controlled Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP) mostly took direction from Moscow; de Gaulle’s Forces françaises libres (FFL) relied on British support. Despite mutual suspicion and occasional betrayals, these fractured groups eventually formed a united front.

By 1944, American leaders viewed de Gaulle as an ungrateful grandstander. President Franklin D. Roosevelt preferred General Henri Giraud as France’s future leader, seeing him as more open to American influence. But Giraud lacked de Gaulle’s political skill. When France was liberated, de Gaulle executed a diplomatic masterstroke: having incorporated the Communists into his Conseil national de la résistance while maintaining British backing, he secured once-defeated France’s place among the four Allied powers occupying Germany, and paved the way for one of five permanent seats on the UN Security Council.

However, unable to shape France’s new constitution according to his strong-man vision, de Gaulle resigned in January 1946, beginning his famous “crossing of the desert.” During this period, France drifted away from de Gaulle’s vision and toward the American-led order. Businessman-turned-statesman Jean Monnet, a close friend of top American figures such as W. Averell Harriman, championed European integration tied to US interests and built the foundation for what later became the European Union—anathema to de Gaulle’s belief in French independence! In 1949, France also joined NATO, even hosting the alliance’s permanent headquarters at Versailles.

The crisis in Algeria then created the conditions for de Gaulle’s return. Military officers staging a coup in Algiers demanded his return, assuming he would keep Algeria, home to nearly 1 million colonists, as a French territory. De Gaulle accepted their call but refused to become a military dictator. Instead, he crafted the Fifth Republic’s constitution, granting sweeping presidential powers. Then four years later he shocked supporters by granting Algeria independence, creating a bitter right-wing fringe that attempted several assassinations and later provided the base on which France’s modern far right prospered (especially in the South, where the de Gaulle-hating pieds-noirs took refuge in 1962).

As president from 1958 to 1969, de Gaulle resumed course and systematically challenged American dominance. He vetoed Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community not once, but twice, viewing the British as mere American proxies. In 1966, he withdrew France from NATO’s integrated command and expelled the organisation from its Versailles headquarters, forcing it to relocate to Brussels. These moves, combining strategy and personal grievance, reacted to the Americans’ attempt to sideline de Gaulle in 1944, which he neither forgot nor forgave.

2/ Nuclear guardians emerged from French technocracy

Energy independence formed the cornerstone of Gaullism. Having seen how oil dependence constrained European powers during the Suez Crisis of 1956, de Gaulle viewed nuclear energy as the key to French autonomy. Relying on American allies in the Gulf was, in his view, strategic submission.

This desire for autonomy extended beyond energy to control over former colonies. A significant part of France’s energy independence came from securing oil and other resources in its former African colonies. Algeria’s Hassi Messaoud field supplied crucial oil, Gabon added further reserves, and Congo-Brazzaville contributed both oil and uranium essential for nuclear development.

These resources lay beyond US control and formed the backbone of what French media called “Françafrique”—a complex web of political, economic, and military ties linking France to its former colonies through resource extraction, development aid, and security guarantees. The shady Jacques Foccart, de Gaulle’s chief adviser on African affairs, orchestrated these often murky but mutually beneficial arrangements from the Élysée Palace.

Yet this strategy would later unravel. Specifically, the oil-based strategy later collapsed amid scandals surrounding Elf, France’s state oil champion. The company financed African political networks and French intelligence operations, leading to corruption trials involving senior figures in the 1990s. One case involved a foreign minister linked to an arms dealer who kept his mistress’s apartments stocked with designer shoes while channeling millions through Swiss accounts. Another concerned an Elf CEO who used company funds to finance political campaigns while cultivating ties to African dictators. Elf was eventually absorbed by its more pristine rival, Total, bringing the scandals to rest.

In contrast, nuclear energy offered a cleaner and more enduring path to independence. De Gaulle himself had established the Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (CEA) immediately after World War II, overseeing both military and civil applications. France then secured its atomic bomb in 1960, joining the nuclear weapons club alongside the US, the Soviet Union, and Britain.

France’s scientific foundations supported this pursuit. Marie Curie’s pioneering work on radioactivity in the 1890s earned two Nobel Prizes, and her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and son-in-law Frédéric Joliot-Curie won their own Nobel for discovering artificial radioactivity. Both were Communist Party members, illustrating the broad political support for mastering this cutting-edge energy source.

But the real transformation came when nuclear power was entrusted to the corps des mines, a little-known but extraordinarily prestigious state engineering corps.

The corps des mines traces its origins to Napoleon’s vision of state-directed industrial development. Initially tasked with supervising mining across the empire, it evolved into the premier destination for France’s brightest engineering graduates. Each year, roughly 400 of the nation’s most gifted students enter École Polytechnique, a top military engineering school. Then after two years of intense competition, only the top 10 graduates—around 2.5 percent—join the corps des mines.

These élite engineers progress methodically through the system. They start by supervising low-level operations across the energy sector—inspecting mines, overseeing safety, and learning industrial processes from the ground up. They then rise through state agencies and state-owned energy companies to the highest positions in industrial policy.

Two features made the corps des mines uniquely suited to nuclear stewardship. First, it operates as a true corps—a small, cohesive group where members know one another personally, sharing sensitive information and coordinating complex decisions. Second, its prestige and legal entrenchment transcend political changes, ensuring continuity across decades.

This permanence addresses nuclear energy’s defining challenge: it is forever.

Once you’re in, you can’t go back because reactors take decades to decommission, sites remain radioactive for centuries, and nuclear waste stays toxic for millennia. Over such long spans, private companies collapse; agencies are reorganised; nations fall or transform. By contrast, the corps des mines was envisioned as an elite order capable of passing responsibility from generation to generation, to guard France’s nuclear programme for eternity—like the knights protecting the Holy Grail in the third Indiana Jones film.

If oil belonged to the world of shady deals and corruption, nuclear was different: it carried a certain cachet, the aura of science and state grandeur, guarded not by arms dealers or politicians but by an elite technocratic order of modern knights of the realm.

In this spirit, the corps des mines became the institution entrusted with France’s nuclear programme. Nuclear power was the grail—a quasi-infinite energy source to free France from dependence—while the ingénieurs des mines served as its enduring protectors. As the following sections show, many key figures in this secret history emerged from their ranks, combining technical mastery with institutional authority to build the world’s most successful civil nuclear programme1.

3/ Single grid operator EDF consolidated France's fragmented electricity sector

The other important element in this story is that France had one single grid operator from 1946 onwards, a company known as Électricité de France, or EDF.

This consolidated approach emerged from several crucial trends converging in post-war France. Reconstruction after 1945 demanded a top-down, command-and-control approach with massive financial resources that only the state, supported by Marshall Plan funding, could provide. The fragmented pre-war electricity landscape proved wholly inadequate for such ambitions. Before 1946, electricity was managed by roughly 200 production companies, another 100 transport operators, and about 1,150 distribution firms, alongside an estimated 20,000 concession-holders providing equipment and services under various local agreements.

In addition, the pre-war industrial élites had largely discredited themselves through collaboration with Nazi Germany during the occupation. By law, individuals whose names were associated with collaboration could not stand for election or be appointed to lead state-owned companies. This purge thus opened the way for fresh leadership emerging from resistance networks.

In the end, consolidation under a single state-owned company achieved four strategic objectives: it created the critical mass needed to modernise France’s electricity grid; it enabled the replacement of discredited industrialists with young, idealistic technocrats fresh from the Resistance; it provided direct access to state coffers for the necessary capital investment; and it allowed the behemoth that EDF became to weigh and carry through major decisions in exceptional circumstances, as we shall see with nuclear policy in 1969.

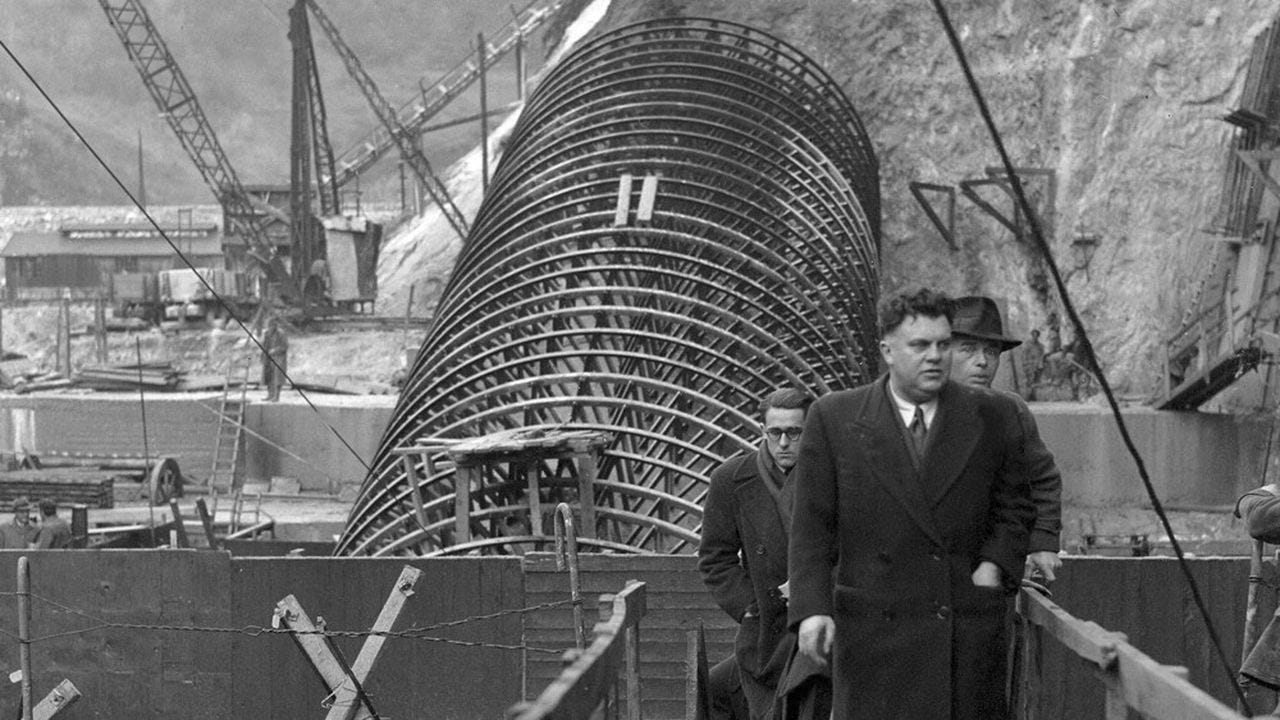

The law creating EDF was promulgated on 8 April 1946, transferring control of around 1,700 smaller energy producers, transporters and distributors to the new national monopoly. Marcel Paul, the Communist minister of industrial production, appointed Pierre Simon as the first président-directeur général. Simon was a polytechnicien and ingénieur des ponts et chaussées who had specialised in hydroelectric power and worked on the pre-war plan to expand France's electrical infrastructure. EDF’s first board meeting took place on 14 May 1946.

EDF’s creation also benefited from an unexpected political alignment between the two dominant forces emerging from the resistance. On the right stood de Gaulle's movement, later organised as the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF). The traditional conservative right had been decimated by its compromises with the Vichy regime, leaving de Gaulle's more iconoclast followers to dominate that political space. On the left, the French Communist Party commanded extraordinary influence, winning 26.2% of votes in October 1945, 26% in June 1946, and achieving its historical peak of 28.3% and 182 seats in November 1946—making it the largest single party in the Chambre des Députés.

EDF represented a perfect political compromise between Gaullist and Communist visions. For de Gaulle, having the entire electricity grid under direct state control was extremely appealing, especially given his obsession with energy independence. State ownership provided the manoeuvring room he deemed essential for national autonomy. For the Communists, state control fitted their ideological framework perfectly whilst offering practical advantages. They recognised the opportunity to transform EDF into a union stronghold, and indeed, a substantial portion of EDF employees became affiliated with the Communist-controlled CGT union. For decades, as reported in French media, EDF’s massive resources were tapped—through various legal and semi-legal mechanisms—to fund the broader French labour movement, closely linked to the Communist Party.

This political consensus proved remarkably durable. The 1946 Constitution's preamble enshrined principles that legitimised this approach, stating that “Any asset or enterprise whose operation has, or comes to have, the characteristics of a national public service or a de facto monopoly must become the property of the nation.” EDF thus gained constitutional protection for its monopoly status.

Twenty-five years later, in 1969, this institutional foundation greatly facilitated forging consensus on France's nuclear acceleration and EDF's central role in executing it. In effect, the political and institutional framework established in 1946 had created exactly the vehicle needed to implement the most ambitious civil nuclear programme in history.

4/ The decisive moment arrives in 1969

This institutional foundation paved the way for the pivotal decision that occurred in 1969. By then, de Gaulle had just left the political stage. On 27 April 1969, French voters rejected his constitutional reforms by 52.4% to 47.4%—a narrow but decisive defeat that shattered the proud general's authority. De Gaulle was a man who could not tolerate such defiance from the nation he believed he embodied. Within minutes of learning the results, he announced his resignation in a laconic statement from his adopted hometown Colombey-les-Deux-Églises: “I will cease to exercise my functions as president of the Republic. This decision will take effect today at midday.” He retreated to his nine-acre estate, La Boisserie, never spoke publicly again, and died the following year at age 79, leaving his presidential memoirs unfinished.