Why Manufacturing Is Harder Than You Think

The West needs more than money to rebuild its factories

Manufacturing has become the new frontier of geopolitical competition. Not the nostalgic version of assembly lines and lunch pails that politicians invoke, but something harder: the fusion of advanced engineering, AI systems, and process knowledge that determines who controls the technologies of tomorrow. The West's belated recognition of this shift—evident in gatherings like this week's Reindustrialize Summit in Detroit—comes as China has already spent decades building an insurmountable lead.

I've been tracking this transformation through several lenses: China's evolution from copycat to manufacturing superpower, Apple's mastery of global production networks, and the strategic competition now reshaping industrial policy. These threads—explored in my recent work on advanced manufacturing, the end of the global factory, and the return of the trading houses—converge on a simple question: Can the West rebuild what it so carelessly dismantled?

Today’s edition is a synthesis of my manufacturing series so far. It makes three arguments:

First, manufacturing has become strategically vital again, determining not just economic outcomes but national security and technological sovereignty.

Second, the West faces structural contradictions that make reindustrialisation nearly impossible under current economic rules.

Third, despite these constraints, practical paths forward exist—from joint ventures to new financial models designed for manufacturing's unique demands.

1/ Manufacturing thrives where engineers rule and workers are trained to think like them

My friend Dan Wang has an upcoming book about China as a nation of engineers, titled Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future. It builds on years of on-the-ground research that have made Dan one of the sharpest analysts of how China became a tech and manufacturing powerhouse.

I owe him the concept of “process knowledge”, which I’ve often drawn on in my writing. The true output of a manufacturing sector isn’t just physical goods—it’s the know-how embedded in people. This process knowledge—the hard-won, intuitive grasp of how to make production smoother, faster, and more reliable—can’t be captured in manuals.

This is what I explored in depth in my analysis of China's manufacturing transformation: how the country didn't just copy Western technology but built an entire ecosystem designed to accumulate and spread process knowledge at unprecedented scale.

In Breakneck, Dan expands on that idea and turns it into a broader study of China's engineering mindset. He writes:

New public works—roads, bridges, dams, entire new cities—are Beijing's solution to any number of quandaries. China's leaders are not only civil engineers: they are also social engineers, bringing a literal-minded approach to implementing the one-child policy and zero-Covid.

This resonates with me not just because I was trained as an engineer and still carry that mindset, but also because I grew up in France—a country that, like China, celebrates engineering. Napoleon helped embed that tradition, and it lives on today in France's ability to deliver large public works projects. For a long time, France was also governed by engineers, just as China is now.

Engineering culture extends beyond leadership—it requires an entire education system that produces technically skilled workers at scale. China graduates over 4 million STEM students annually, with 1.6 million in engineering alone. More critically, its technical and vocational education system trains millions more in practical manufacturing skills. These workers understand precision, quality control, and continuous improvement as second nature.

The West dismantled much of this infrastructure over decades. Vocational schools closed as manufacturing jobs disappeared. University systems expanded but focused on producing lawyers, financiers, and consultants rather than engineers and technicians. Even remaining engineering programmes often emphasise theory over hands-on production experience. Meanwhile, parents steer children away from “dirty” factory work toward “clean” office jobs, creating what Dan calls “lawyerly America” versus engineering-focused China.

France may have lost ground in other areas, but unlike America, we French immediately understand why China is obsessed with building, how its engineering culture helped it master manufacturing, and how that culture has turned it into the world's leading export-driven industrial power.

Rebuilding this culture—from elite universities down to technical schools—represents a generational challenge the West has barely begun to address.

2/ Software becomes the servant, hardware rules

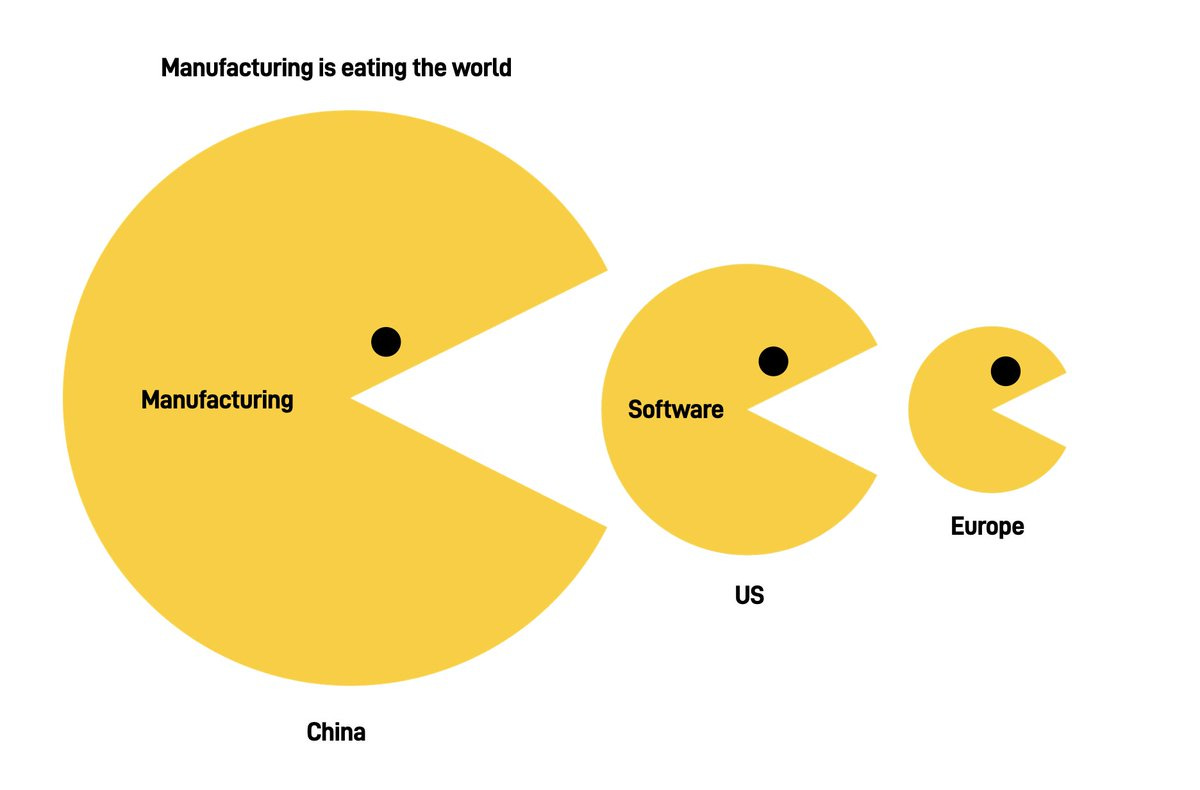

The West may have turned its back on manufacturing to focus on less tangible pursuits such as financial services and software. But the moment we are living through marks a reshuffling of the cards. As David Galbraith noted earlier this year, “manufacturing is eating software.”

Software creates value and reshapes industries by orchestrating data across many devices, then feeding that data back into the system. This forms a feedback loop of operational intelligence, driven by the power of network effects.

But not every industry can support this kind of loop. There is what we might call a capital-to-intelligence gradient—a scale showing how much investment and skill it takes at the operational level to generate useful intelligence.

At the low end, platforms like TikTok, YouTube and Facebook gather insight from millions of users with little more than a phone. Further along, Uber and Airbnb depend on drivers with cars, and hosts with property. At the far end lies manufacturing, where every step depends on factories, months of training, deep process knowledge, and strict quality control.

In other words, manufacturing faces a fundamental constraint: each new node in a manufacturing network demands massive upfront investment and ongoing costs for materials, labour, and equipment. Unlike software platforms where adding users costs almost nothing, in manufacturing every factory, production line, and unit of output carries substantial expense.

Obviously, software can still contribute to increasing returns in manufacturing by creating feedback loops that improve efficiency and output over time. This happens in two ways:

First, it embeds inside the factory. With no crowd of users to draw on, manufacturers use sensors, actuators, and dashboards to monitor and optimise production. This forms a closed-loop system where the factory learns from its own data.

Second, software embeds in the product—for instance, in electric vehicles—creating a second loop of feedback once the product enters the world.

Yet software cannot bring marginal costs to zero as it does with online applications used by hundreds of millions of smartphone users. Manufacturing remains bound by materials, yield, throughput, and reliability. Physical constraints persist.

In short, hardware now sets the terms. As software becomes cheap—or free—to reproduce, it is bundled into physical products but no longer drives the business. Software is vital, but it is no longer the competitive edge. The real competition shifts to hardware, where cost, quality, and scale decide the outcome.

This reflects Clay Christensen's law of conservation of attractive profits: when one layer of a system becomes modular and commoditised, profits move to the adjacent layers. In manufacturing, software is now the modular layer. It is needed, but no longer a competitive advantage. Profits—and power—now belong to those who can master hardware at scale.