Venture capital has always been an American game played with American rules. Silicon Valley sets the terms, defines success, and draws the world’s best entrepreneurs into its orbit like a gravitational force. For European founders, this creates an existential question: do you stay local and risk irrelevance, or go global and risk losing everything that made you unique?

Martin Mignot understands this tension better than most. A partner at Index Ventures, he’s spent the last three years building their New York office after a career in London, helping European companies navigate the treacherous waters of US expansion. Index itself embodies this challenge—a firm born in Geneva that had to become truly transatlantic to compete at the highest level. Today, they’re arguably the best venture capital firm in the world, with recent exits including Figma, Scale AI, and Wiz.

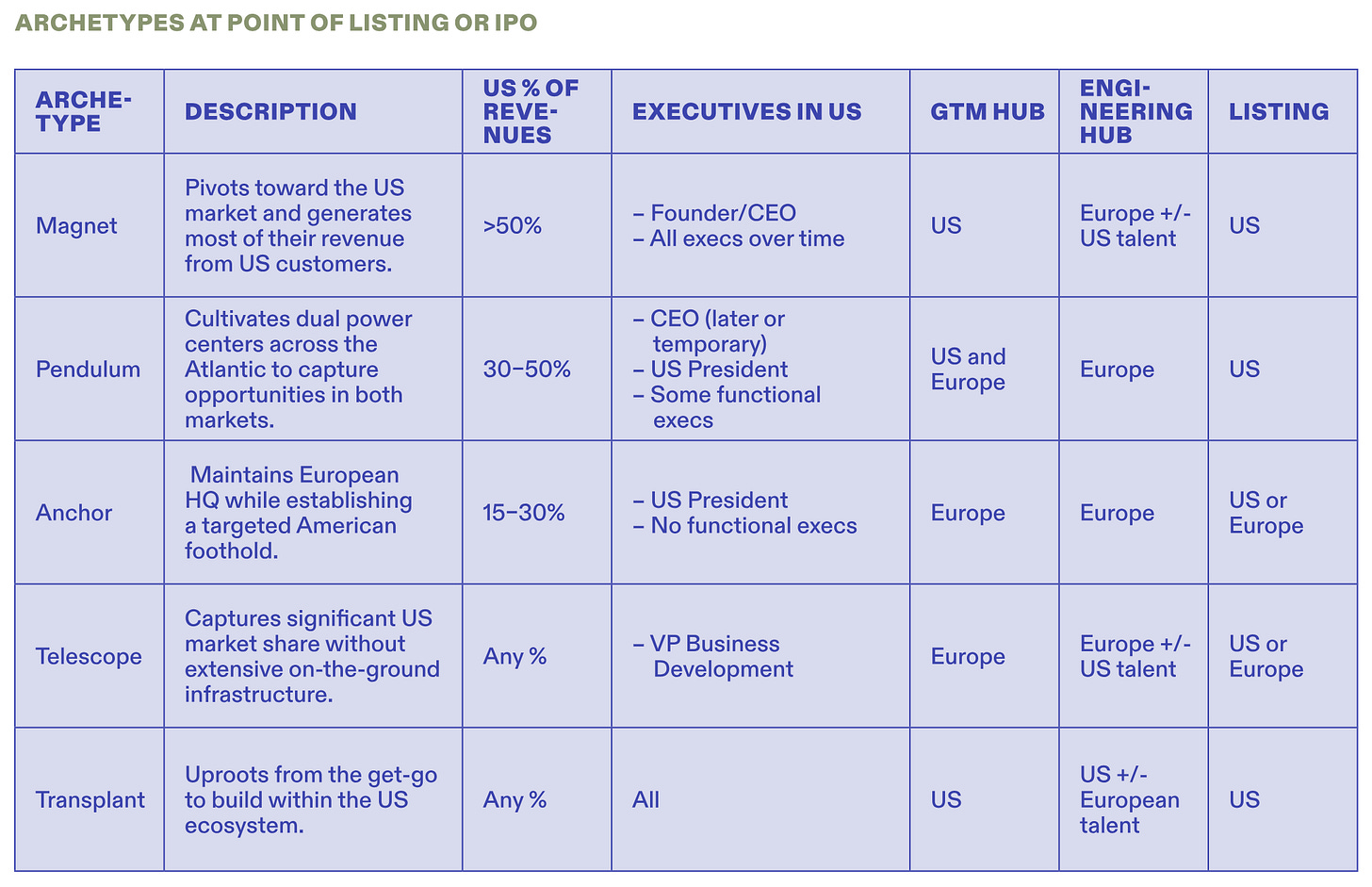

This summer, Index published Winning in the US, a data-driven playbook for European and Israeli companies expanding to America. The book’s breakthrough is its recognition that there’s no single path to US success. Instead, it identifies four distinct archetypes—‘Telescope’, ‘Magnet’, ‘Pendulum’, and ‘Anchor’—each requiring radically different strategies. A gaming company can conquer America from Helsinki; an enterprise software startup must transplant its founders to San Francisco. Get the archetype wrong, and you’ll burn millions trying to force the wrong playbook.

But what struck me most in our conversation wasn’t the tactical advice about hiring or go-to-market strategies. It was Martin’s observation about the fundamental asymmetry between Europe and America: Europeans obsess about American politics, culture, and market dynamics, whilst Americans barely think about Europe at all. This indifference is both liberating and terrifying. It means European founders won’t face the political backlash they fear, but it also means they’re starting from absolute zero—unknown, unproven, and irrelevant until they prove otherwise.

This conversation with Martin, recorded in September, explores what it really takes for European companies to succeed in America, why so many fail by hiring the wrong “head of US,” and whether the current geopolitical tensions matter less than we think. The transcript has been edited for flow and clarity.

“It’s an overnight success a decade in the making”

Hi, Martin. Nice to see you.

Good to see you.

Martin, we go way back. We’ve known each other for twelve years now. You were already working at Index when they invested in my firm, The Family, back in 2013. You’re still at Index and have become a partner since then. You used to be in London but are now in New York, or between New York and San Francisco—perhaps you can tell us more about that.

Before we discuss the book, Winning in the US, which Index published in July, we should start with a few words about the firm. I won’t name names, but this summer I had breakfast with someone in the US who told me, between us, that Index Ventures has probably become the best venture capital firm in the world. That’s because you’ve had tremendous results recently: lots of portfolio companies going public, lots of visibility in the media, clearly very strong tailwinds, and a very strong presence both in Europe and in the US. You don’t have to comment on the praise, but tell us more about Index Ventures.

Well, first of all, it’s obviously very nice to hear that. I think it’s true that we’ve had a really strong start to the year with the IPO of Figma recently, where we were the largest shareholder; the investment of Meta into Scale AI, where we were the second largest shareholder; the offer by Google to Wiz, where we were the largest shareholder; and the Dream Games operation. So we’ve had a lot of very big outcomes, all in the past six months. But obviously, as you know, in venture it’s an overnight success a decade in the making. Most of these companies—we’ve been in Figma since we led the seed round when Dylan was nineteen. That was over twelve years ago. So these successes are a very long time coming. It just happened that a lot of these transactions are all happening at the same time, but they’ve been very long processes.

Regarding Index, we’ve been doing early stage tech investing for about three decades now. We’re actually celebrating our thirtieth anniversary next year in 2026. We started originally out of Geneva, which will be relevant to the conversation we have today. In a way, starting from a place like Geneva, where there is little to no homegrown tech mega-success, forced us to be global from day one. That was very much the original idea: to bring West Coast, Silicon Valley investment style to the rest of the world, with the simple idea that great entrepreneurs could come from anywhere where you had talent, infrastructure, and resources.

That forced us to look outside. Our first big successes were actually in places like Finland with MySQL, Estonia with Skype, and Sweden with King, which were not prime locations at the time for tech investment and tech entrepreneurship. Then from that strong starting point in Europe, we very quickly expanded back to the US. Today, we are a totally transatlantic fund. Half of the team is in the US, half is in Europe. We invest a little bit more in the US, but it’s roughly half and half. It’s a very balanced, fully transatlantic fund that operates as one team across all those geographies, which is a bit different from a lot of other funds.

“It’s much easier to be born global than to become global”

Index has been publishing various books over the past few years. I know the team who’s been working on it—it’s a lot of work because for each book, you go and interview dozens of portfolio founders and beyond, collecting testimonies and data. It’s all beautifully made. The book Winning in the US is a very nice object.

Tell us more about the book, and maybe we should spend some time discussing the “archetypes”. I think it’s really a breakthrough in the book because startups form such a diverse world. So many startups fail because they apply recipes they’ve read somewhere that don’t really apply to their particular context. You’ve made the effort to distinguish between different types of startups, which you call archetypes. There are four of them, but perhaps it’s worth spending a few minutes introducing each archetype and what playbook being in one bucket or another dictates for founding teams.

Absolutely. Before I get into the nitty-gritty of the archetypes, let me provide some context on the books and on Index Press. The initiative, which we call Index Press, can be found on the Index Ventures website under a section called Press. The driver behind these was that founders always ask us the same questions. Some questions are very specific, but many are not specific to a company—they touch on org design, compensation, option plans, and international expansion. We have a book called Scaling Through Chaos. We’ve done a lot around option plans and compensation in general, and international expansion. We’ve got two books: one is Winning in Europe for US companies expanding to Europe, and this latest book is Winning in the US for European and Israeli companies that want to succeed and expand into the US market.

All these books share the same characteristic and structure, mixing a quantitative approach with qualitative insights. For this book, we studied the expansion plans of hundreds of European VC-backed companies—when they expanded, how they expanded, what team they built, and so on. We coupled that with testimonials, interviewing more than forty top founders like Nikolay Storonsky, Ilkka Paananen, and Daniel Ek, as well as some senior executives, to bring the data to life.

We came up with four archetypes—actually five, but one is a bit different. The fifth one, which I’ll start with, is what we call the “transplant.” These are companies with European founders that started in the US and have been based in the US from day one. Examples include Datadog, Duolingo, and Stripe—not shabby successes, and it’s actually been a very successful archetype. But obviously, that’s not relevant for most European companies. These companies are typically US companies for all purposes, though they also tend to develop quite a bit of European presence over the long run.

What makes a company not a transplant? What stage do you need to wait for before going to the US to fall into the other archetypes?

Any company that was started in Europe, meaning either has a European legal entity or the founders are literally based in Europe with the team based in Europe, even if they incorporate in the US, we would still call them European companies. The transplants are very much US-registered companies whose founders and early team members are all based in the US. They are US companies for all purposes, though some of these founders may be dual citizens. That’s a different category.

The book focuses more on the four other archetypes, which are European-started companies that then expand to the US. These archetypes depend mostly on two things: the size and importance of the US market for the business in the long run, and the go-to-market approach—whether it’s marketing-led or sales-led.

Can you explain in concrete terms what it means to be marketing-led? People may confuse the two categories.

On one extreme, you have what we call the “telescope” companies. These are marketing-led companies where the US is a large part of their market. Examples include gaming companies like King, Supercell, and Voodoo in France. Because of the app store and marketing channels, especially performance marketing that are global, these companies can scale globally, including in the US. The US is their largest market but not the dominant market. They can do this all from one location, which can be anywhere—Paris, Stockholm, or Helsinki. These have been some very big successes. Anything in consumer mobile, with gaming being the biggest, follows this approach. These companies tend to keep most of their team in Europe. Everything is very Europe-driven. Over time, when they get bigger, they may hire a few senior folks in the US for product angles or business development relationships with Meta, Apple, Google, and TikTok.

Those are the companies you buy from to raise awareness and convert customers.

Exactly. They’re your distribution partners, so you want to be close to them. But apart from that, most of the team stays in Europe.

On the other extreme of the spectrum, very sales-driven companies where the US is the vast majority of your market, especially early on, you have what we call the “magnet.” These are typically enterprise software companies, especially if you’re selling infrastructure-related products or truly global solutions like cybersecurity. Examples from our portfolio include incident.io and Collibra. Most Israeli cybersecurity companies follow this model, and Datadog in France would be a good example. These companies start in Europe and build their first work there, but there’s such a pull from the US market that very quickly the founding team ends up having to spend most of their time in the US, moving there either part-time or full-time, building at least a go-to-market team, and eventually moving more and more senior leadership to the US.

That’s because in those segments, sales means presence at a very senior level. The CEO or very senior people need to be there to meet potential customers, convert them, and prove they mean business.

Exactly. That’s what we mean by sales-driven versus marketing-driven.

Then you have two others in between these extremes. One is the “pendulum”—companies that started in Europe. Index, in a way, is a pendulum. These are truly balanced companies where the US becomes close to half of the business, maybe slightly more or less, but Europe remains very important, as does the rest of the world. Examples include Spotify and Celonis. These companies build significant teams on the ground in the US but also have significant teams in Europe and never truly make a choice. If you look at Daniel Ek, he’s a really good example—he literally spent half his time in the US and half in Europe when scaling Spotify in the US. These businesses live on both feet and keep strong presence on both continents.

Finally, you have the “anchor” model, where Europe remains the dominant geography. The senior executive team remains in Europe, and the largest market remains European. But the US grows over time and there’s a pull, though it remains a smaller portion of the overall market. Adyen is a good example—the founding team is still in Europe, and most of the market is European, even though the US is growing very fast. Eventually, you can think of it as being served from Europe. Revolut is another good example where Europe remains the largest share of the market. These are typically in industries that are very big domestic sectors where you can build a hundred-billion-dollar company just in Europe, even though you will have some global presence. Fintech is obviously a case study of that.

There’s another framework I’ve been using a lot, which is to distinguish between “default global” and “default local.” You have to be aware of this. When you start, depending on the market you’re trying to address and the industry you’re part of, if you apply a local playbook to a business that’s meant to be global, it usually fails. Fintech is very much default local because you need to address a market that’s local due to regulations and culture—the relationship with money and banking—and you can’t really succeed otherwise.